Billy Mavreas’s Tibonom is one of those works of art determined to move beyond its own bounds—casting, through mood, tone, and implication, a specific kind of spell. The collection of silent strips, serialized mostly in a yoga magazine some years back, is held together in each installment less by narrative than through an air of formal consistency and thematic focus: the title character, labeled "boy priest," seems to be a kind of tweenage druid, and navigates the world alongside a faceless, catlike creature referred to in Joe Ollmann's introduction as Lifeform.

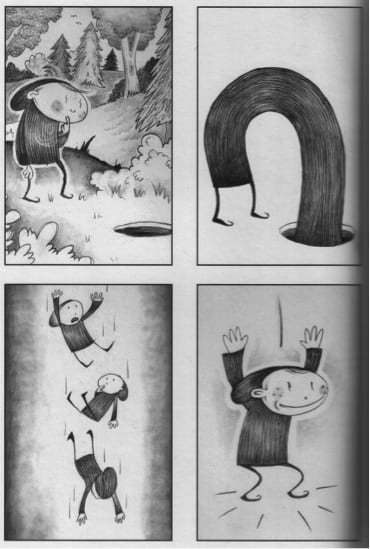

The bulk of the book is made up of wanderings, meditations, and daydreams; the work is quiet, and very internal. Mavreas’s pencils bear the look of gray washes, elaborating a simple world with a graceful sense of texture, the nuances of which are this comic’s finest part. These artful smudges surround the characters often with delicately rendered auras (one of the strip’s few constants is the porousness of the characters’ psychic borders). This spongy qualty allows the artist to delineate thoughts and feelings through floating, faintly penciled shapes, abstractions which indicate the shifts in the characters’ minds, and Mavreas’s. The artist seems particularly taken with what moves the mind or spirit, and within the rigidity of the strip’s window-like four-panel structure (implying its own kind of symmetry), Tibonom’s soul, or ego, is altered often. More than once it’s dissolved or warped and transported—a phenomenon to which both he and reader can respond only through openness, an agreement to be flexible.

Yet even with all this constant shifting Tibonom’s springtime world remains placid, like a child’s drawing swapped out at points for—as above—more lucid, harsh, and tempting daydreams. It may be that these reductions stem from our seeing through the boy-priest’s eyes, or that in comics this simplification is simply natural. But it seems a loss—especially when the artist shows such skill with landscapes—that the panel’s backgrounds serve rarely as more than a springtime stage, an affectionately rendered archetype atop which the author toys with the boundaries of thought and form.

This makes the strip feel very internal, even nostalgic, comfortable with abstract manifestations of the unexpected but less so with the concrete: the things that same inward focus might serve to counter; those everyday, distracting interferences; life’s constant static. If there’s a deeper problem here it lies in a recurring sense of reassurance, coming off the strip’s broader rendering of an over-simple world, and the fact that resolution (or lack of consequence) of any stressors is so very nearly a constant. The risk of this—which would be greater were the strip more narratively driven—is that of rendering the entire work irrelevant. This world, so nearly innocent, feels far afield from the world we live in, less for its sense of fantasy than through its level tone.

But the book’s indicia suggests its shelving in the “Literature for children” section, if not in “Comics” or with “Spirituality,” so perhaps it’s only fair to take the strip’s world as subjective. For the vision of simplicity achieved, along with its accompanying sense of imperviousness, may be a matter of one’s frame of mind. This frame isn’t observed so much as heartily recommended; even while essaying at exploration, Tibonom is a work of advocacy. Specifically, it preaches a calm acceptance of outward problems, an embrace of the unknown, and a questing towards an inward balance, or (depending on the reader) the spiritual, or infinite—may indeed create. If this all seems fuzzy or positivist in its guarantees of comfort (as it can and does to me), it’s tempered still by placid and wise-seeming warnings. More than one of Tibronom’s short arcs implies, thankfully, that as visionaries and people we have our limits—there are little betrayals that happen here, and small griefs exposited and quickly diminished. This shrinkage of life’s problems to a sort of game may be what most diminishes the work, but it’s also both its endgoal and what makes it serve, both for believers and us cynics. In toying with this stuff, the stakes are low—as in most games—so there’s little harm in trying.